This story was originally published by Curbed before it joined New York Magazine. You can visit the Curbed archive at archive.curbed.com to read all stories published before October 2020.

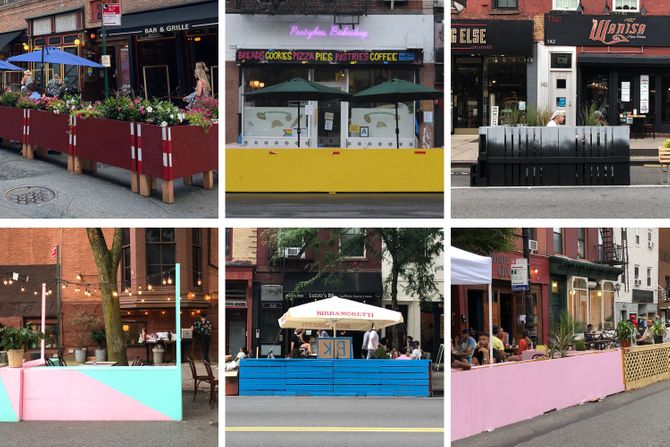

A couple nights ago, like many nights during the pandemic, I went on a bike ride around Brooklyn — down the same streets I always do. Just a few weeks ago, they were deserted, but now they’re lively and filled with new additions to the built environment: so-called “streeteries” comprised of planters, vibrantly painted sheets of plywood, jersey barriers, picket fencing, cinder blocks, trellises, and all sorts of materials that someone could scrounge up at a hardware store in a pinch.

These parking spaces turned outdoor restaurants are New York’s latest examples of COVID-19-inspired improvisational architecture — evidence of resourcefulness and creativity with limited means. They also hint at what the post-pandemic future might hold: a city life that’s more aesthetically vibrant.

I personally don’t feel comfortable eating in any of the open restaurants yet, given the spread of COVID-19 is still an issue. (And who would want to be the infamous brunchers drinking mimosas when the real, and urgent, work of protesting is still happening in the streets.) But, to me, these streeteries are among the most exciting designs to enter the public realm in a really long time. That these restaurants, many of which have had little or no income for months, have built comfortable outdoor spaces practically overnight is truly a testament to resilience.

On June 22, New York City entered phase two of reopening, which allowed outdoor dining. (We’re now in phase three.) In the early days of the reopening, some restaurants and bars were making do with makeshift solutions, including using beer kegs as barriers and seating. Eventually, the city’s Department of Transportation issued guidelines for open restaurants which included specifications about social distancing, safety, and accessibility. Businesses are now able to implement changes and “self-certify” that they met the requirements. The results are hit or miss, though, with some restaurants going the extra mile to create beautiful and accessible environments and others just placing a few flowerpots and chairs on the streets.

A few common trends I noticed: colorblocking, lots of plants, a cottagecore look, an Animal Farm aesthetic (wood trellises and slatted enclosures), construction site chic, and a handful that stuck to basics.

On Smith Street in Cobble Hill, a block of adjacent restaurants all appeared to have worked with the same builder — all of them had trellises topped with a few potted plants which made their outdoor spaces feel like gardens. Brooklyn Pizza Market made their barriers unique by repurposing tomato cans into planters. Xochitl Taqueria painted their plywood enclosure a buttery yellow. On Fifth Avenue, one restaurant painted its barriers white and decorated them with cascading flowers and vines — cottagecore in the wild. I also really enjoyed the Barragan-esque bright pink Cubana Cafe used for their outdoor area. Café Grumpy, a coffee shop on Seventh Avenue in Park Slope, used shipping pallets to enclose their seating area.

These improvised spaces offer refreshing breaks from the relentless blandmarks and towering luxury condos that have defined the city’s new architecture for the past few years. Meanwhile, these open restaurants have also accelerated a stalled conversation about reducing on-street parking, which seems always to result in fiery debate. None of the streeteries I passed were blocking the bike lane, and it felt a lot nicer to bike past people eating than it would to bike past parked cars — one of which might unexpectedly open a door or pull out in front of me.

In her book A Paradise Built In Hell, Rebecca Solnit praises the ability of people to create new systems during and after crises. One of her conclusions is that communities, not official channels like governments and corporations, achieve positive change quickly and effectively when they have the freedom to do so. “They demonstrate the resilience and generosity of those around us and the ability to improvise another kind of society,” she writes. This is a hopeful thought. (That said, her framing of this immediate timespan as “disaster utopias” is troublesome, as is a tendency to use the bootstrapping of communities to validate the failure of government.)

Over the past few months, the outbreak of COVID-19 has required communities to improvise and reinvent nearly every aspect of city life, resulting in incredible changes to New York City’s built environment. Community fridges are popping up to tackle long-standing food insecurity and food waste problems and have become neighborhood beacons. Mutual aid networks, formed rapidly at the onset of the crisis, have adapted to sustain the work they are doing to help their communities long-term. Streeteries are just another example of that improvisation. Elsewhere, the changes from improvisation has led to new murals and the removal of racist symbols.

Before moving to New York about seven years ago, I lived in San Francisco, which has been building official “parklets” — pocket-size parks in parking spaces — for nearly a decade now. What began as a creative project to reclaim public space — a design collective named Rebar laid out sod and chairs in a parking space and kept feeding the meter — has turned into a wildly successful municipal program. Some of my fondest memories of San Francisco were made in the parklet outside Devil’s Teeth Baking Company, which was designed by Juniper Architecture.

The ad hoc New York City streeteries are a different breed than the architect-designed, officially sanctioned San Francisco parklets, but the latter demonstrate how these new players in the streetscape might evolve.

When I ride down the street in the post-pandemic future, perhaps there will be even more visual vibrancy from interventions like streeteries (perhaps even publicly commissioned parklets). However, there’s a certain magic to these DIY designs that more formal constructions would likely erase. So, for now, I’ll appreciate the charm of these ad-libbed solutions, and tip my hat to my fellow New Yorkers who have used their creativity to make the city more livable.